Lindsay Montgomery

Lindsay Montgomery is an artist and ceramicist based in Toronto, Canada. Here she speaks to Nicola Waterman about her latest work, the impact of COVID on women and how work created 500 years ago is still relevant today …

As though she had the gift of foresight, Lindsay Montgomery set up her studio space at home in Toronto not long before the COVID pandemic began. Despite the tough lockdown measures imposed in Canada, with a reliable local supplier still able to deliver all the materials she needed, Lindsay describes 2020 as a fruitful time for her - a year in which she was more prolific in her practice than she’d ever been in the past, producing a whole solo show, ‘Year of the Flood’ (Galerie 3, Quebec City, 20 March - 18 April 2021).

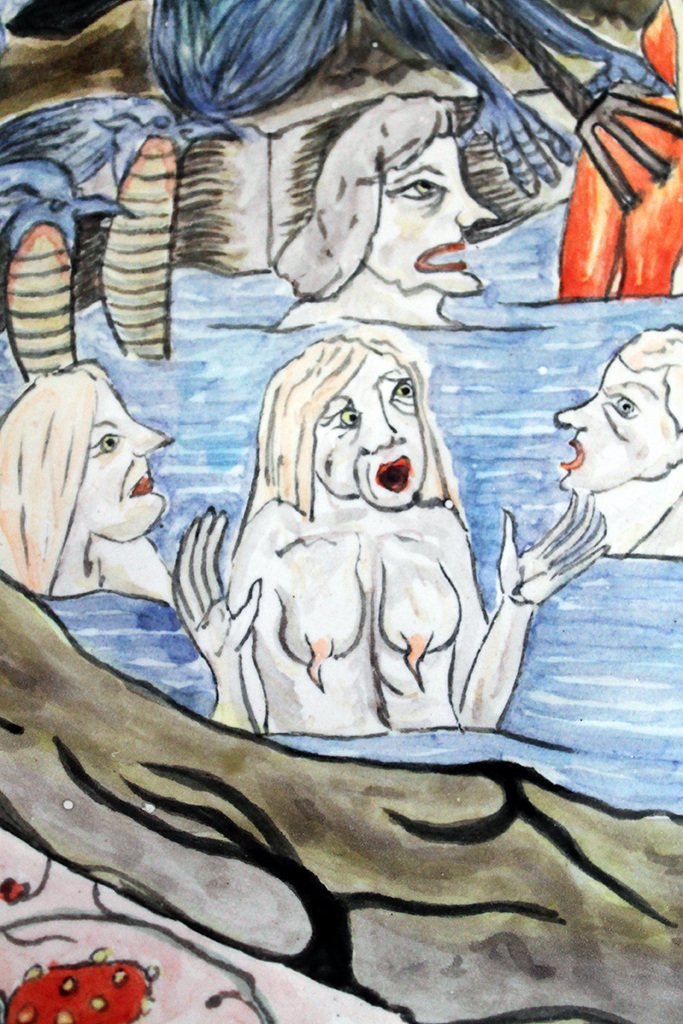

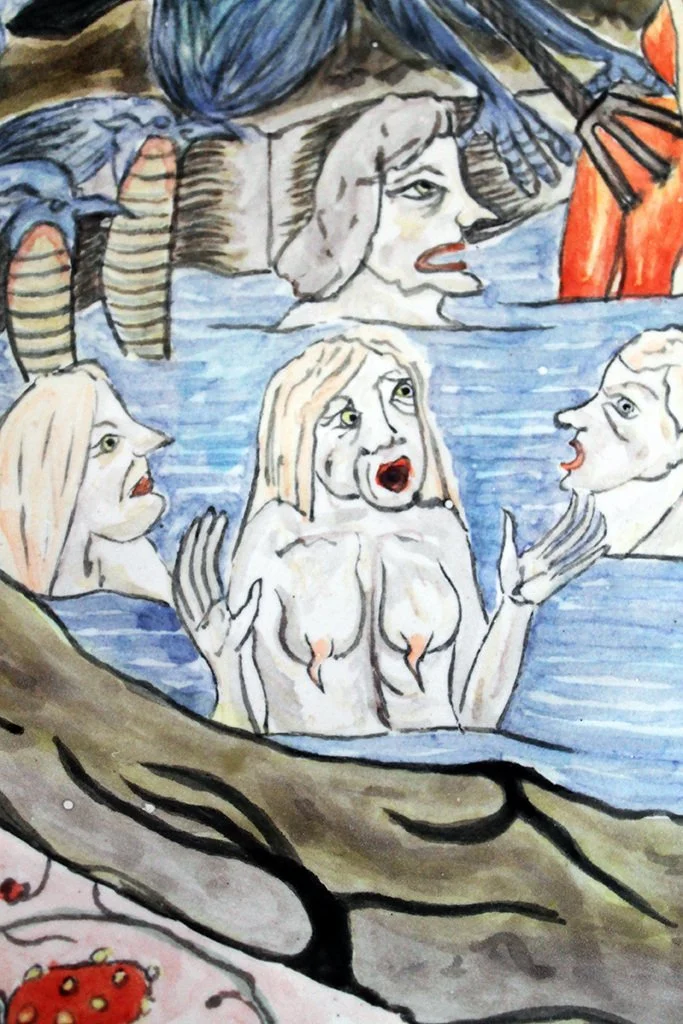

The work Lindsay produced for the show was a continuation of the project she’s been engaged in since 2016, what she calls her neo-istoriato series:

… it’s a series of objects that re-imagine Mediaeval manuscript illustrations and Renaissance imagery, all [painted] on forms that are taken from various European cultures - their tin-glazed traditions. So, it’s a type of ceramics, and historically it was meant to be a way to communicate the most important myths and allegories of the time.

The series was prompted by Lindsay’s interest in the period, and also the idea that it was then that we - humankind - seeded the problems we’re still dealing with today, including climate change and misogyny. Looking at the images used on the original istoriato, Lindsay found herself thinking, ‘Wow, things really haven’t changed that much!’ On the relevance of these pieces to a modern audience, Lindsay goes on to say:

It’s interesting to think about how far we’ve come technologically, but sometimes it really feels like our culture - our cultural ideas and cultural norms - haven’t caught up. So it’s a really strong way of reminding people that you can look at this image from hundreds of years ago, or this object that was meant to do something important to a culture hundreds of years ago, and have it still feel so relevant now.

Over the years Lindsay has amassed a huge collection of Mediaeval and Renaissance imagery, which inevitably (given its prevalence at the time) includes a lot of plague imagery, and she says it felt natural, with the arrival of COVID, to start featuring these images in her work:

It felt so relevant at that moment before we had vaccines - it was really like this idea of magic in medicine and … this idea that we were looking for essentially this magic potion that would help us move out of this terrible situation.

Created at the height of the first lockdown, one such plague-inspired piece She-cession (2021) speaks not to the search for a vaccine, but the disproportionately heavy burden COVID placed on women. The round charger shows Death mounted on a bull riding across ground strewn with prone women. While 2020 was a period of creative fruitfulness for her, Lindsay is acutely aware that this was not the case for many women. Talking about the piece, Lindsay says:

I was watching my female friends … take this step back from their careers, if not leaving them entirely, because the bulk of childcare and responsibility for looking after the family came down on them. I can’t tell you how many of [them] were working 16 hour days every single day during lockdown because they had 8 hours of work they were expected to do, plus [homeschooling] … and we started to hear this term, ‘she-cession’ [a recession in which women’s unemployment is higher than men’s] because there was such a fear that women would not return to the workplace.

That this level of gender inequality (if not downright misogyny) persists in the 21st Century does rather prove Lindsay’s point that ‘things really haven’t changed that much’ since the original istoriato were produced.

‘She-cession’ - Round charger (2021)

Not all of Lindsay’s recent work speaks to the pandemic, however. With her 2021 work Crone Jug Lindsay references the traditional Toby Jug (subverting it even, replacing the usual florid, jovial man with a heavy-browed, unsmiling woman), but also explores the idea of the crone as the supreme matriarch, a worship figure, the grandmother:

I think I’ve been saying this to my female friends forever. We’ve always talked about this - the women that we respect the most were our grandmothers, these wise women and the things they have to teach us … I’m always trying to play with this idea of Mother, Maiden, Crone - I think the maiden and the crone are the two that I fixate on because they’re the only ones that I have experience with … it’s constantly moving in my head: imagery about how to talk about the crone, especially.

But the women in Lindsay’s work aren’t always women we can empathise with, worship, or aspire to be; as she says herself, many of her pieces speak to the idea of toxic white femininity, pieces such as Karens (2020).

In 2019, Lindsay was a resident artist at Medalta in Medicine Hat, Alberta, which Rudyard Kipling described as having ‘all hell for a basement’ due to the natural gas fields on which it’s built. Images of the Hellmouth having been prevalent in her work since the beginning, Lindsay loved this idea and was inspired to create her Hycroft Hellware series. The series included Beckys (2019), which was followed in 2020 by Karens.

Mining imagery from Dante’s Inferno (with it’s nine circles of hell), Lindsay recalls coming across one image in particular and thinking, ‘Oh, that looks just like a burning pit full of Karens’. Painted on an oval charger, the piece:

… speaks to this idea that when your ancestral culture is kind of problematic, how can you use your voice to bring awareness to that? That’s always been something that I’ve been engaged with in my practice, and I made [Karens] right at the time when there was that incident with the woman in Central Park and the birdwatcher, and it was the epitome of a Karen: this woman weaponising racism as a way to be violent …

“I think it’s really important for us to talk about what a Karen is, and you don’t want to be like that as a white woman.”

So, what next for Lindsay? With travel restrictions easing, next year will see a return to the residencies that are such an important part of her practice, giving her an opportunity to work at scales not possible in her own studio, and a way to ‘change things up and to meet people’. In Spring 2022 Lindsay will spend two months in France preparing for her first solo show in Europe; despite the number of residencies she’s been on in the past, of this one Lindsay says:

… this is really the first time that I’m going to travel to places that I directly draw lines to within my family ancestry - that’s France and England and Scotland - and I don’t know why I’ve been wary to actually go to these places and really connect with those histories … but I think it’s going to be a really significant period of making for me, and I’m really excited to take part in that.

We’re excited too - to see the works that emerge from Lindsay’s sojourn in France, the ideas that they speak to, and the stories they’ll tell …

Lindsay Montgomery spoke to Nicola Waterman via Zoom on 26 October.

All images courtesy of the artist.